In this article, we set out to analyze the gig economy workforce two between countries of similar socio-ecomomic backgrounds.

Comparing our gig economy findings to numbers taken from reports for the traditional workforce, we attempt to unravel how South Africa and Turkey with similar demographic and socio-cultural makeups, reveal ample differences in the gender distribution of their gig workforce.

Gig workers are a diverse group

It is easy to see why many scholars would argue so, their case being based on the anonymity factor they find advantageous. The reality, on the other hand, is far from the utopian ideal of the gig economy.

Despite the developing interest around the gender and age breakdown of the future of work, a much debated topic in the United States and Europe, there is little evidence to the experiences of groups outside these areas. Therefore, gender and age gaps in the gig economy are a mystery to many.

As with any research for the gig economy, the lack of demographic data is a primary challenge. Analyzing gender distribution based on governmental resources is also difficult, since gig work doesn’t even seem to meet the standard labour force survey definitions of employment (Hunt, Samman, 9).

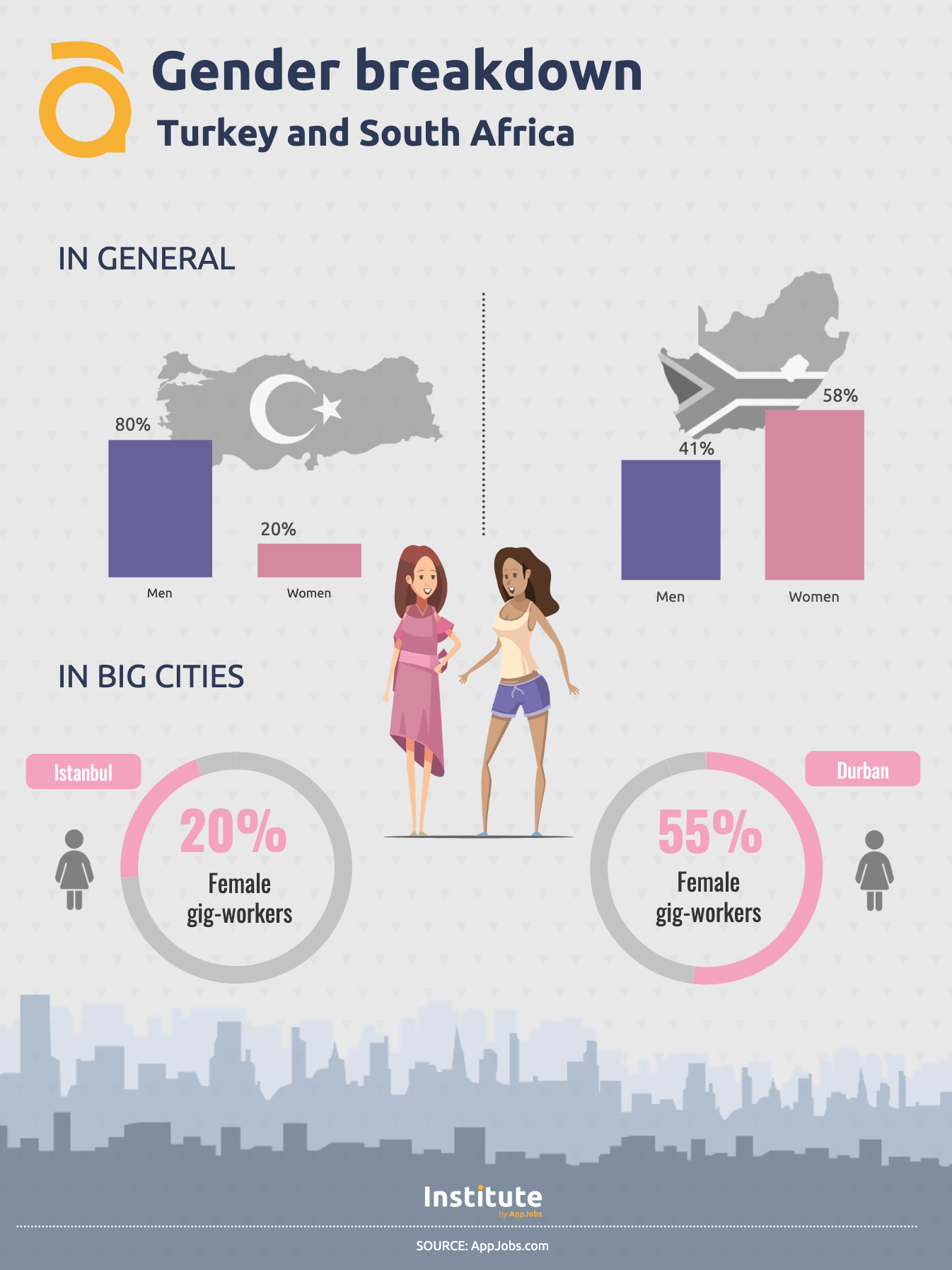

In this case, our best attempt is to back up our analysis with data produced by the AppJobs Institute, based on over half a million members. Below is the gender breakdown of AppJobs members in Turkey and South Africa.

Date range: 1st July 2019- 30th September 2019

It is easy to see why many scholars would argue so, their case being based on the anonymity factor they find advantageous. The reality, on the other hand, is far from the utopian ideal of the gig economy.

Despite the developing interest around the gender and age breakdown of the future of work, a much debated topic in the United States and Europe, there is little evidence to the experiences of groups outside these areas. Therefore, gender and age gaps in the gig economy are a mystery to many.

As with any research for the gig economy, the lack of demographic data is a primary challenge. Analyzing gender distribution based on governmental resources is also difficult, since gig work doesn’t even seem to meet the standard labour force survey definitions of employment (Hunt, Samman, 9).

In this case, our best attempt is to back up our analysis with data produced by the AppJobs Institute, based on over half a million members. Below is the gender breakdown of AppJobs members in Turkey and South Africa.

Istanbul leads the list with 88% male workforce. In Turkey as a whole, men make up 80% of Turkish the workforce.

Durban is at the bottom section of the list with 45% male workforce. In South Africa as a whole, men make up 41% of the gig economy workforce.

The AppJobs Institute reports show us that 20% of the Turkish gig economy workforce consists of women in whereas the percentage is 59% in South Africa. Expecting that gig economy workforce percentages would correlate with the traditional workforce gender demographics, we are surprised to see South African workforce numbers taken from the World Bank.

South African women contributed to 45% of the traditional workforce in 2018. (The World Bank, 2019) Strictly speaking, the percentage of South African women working in the gig economy (59%) is even higher than the percentage of South African women working in traditional jobs (45%).

On the other hand, Turkish women contributed to 33% of the workforce in 2018 (The World Bank, 2019) which as expected correlates with our gender report (27% of the Turkish gig economy workforce is made up of women).

How can Turkey and South Africa reveal such different results?

A hypothesis of why more South African women participate in the gig economy can be explored looking at unemployment rates. South Africa’s unemployment rate over the whole working age population was 29% back in June 2019 (whereas Turkey was 14.1%, according to Trading Economics).

Given that more women participate in the traditional workforce in South Africa than Turkey and that unemployment is higher in South Africa, the gig economy could be seen as a stronger and steady alternative to traditional jobs by South African women.

Additionally, since South African women are more likely than men to be involved in unpaid work (Statistics South Africa, 2018) and are at a higher risk of discrimination at work (Sinden, 2017), it can be suggested that South African women find refuge in gig economy jobs where they presume that they would be facing less bias. Check this blog post to find out more about the The Rise of The Female Entrepreneurs!

Also at a higher risk of discrimination, Turkish women face challenges regarding maternity leave, childcare assistance and social security that make traditional jobs less than ideal (Kagnicioglu, 2017).

Nevertheless, unlike their South African counterparts, Turkish women don’t seem to rely on the gig economy as an alternative. Indeed, the current regulations and policies make all kinds of work undesirable, placing Turkey below the OECD average of 63% share of women who work (Lowen, 2018).

What can be done in order to create a more inclusive gig economy?

While recognizing the innovative features of the gig economy that encourage women’s participation and contribution to economic equality, Barzily and Ben David (2017) point out that the equal and ideal gig economy cyberspace is still utopian.

The added aspect of anonymity is a feature strong enough to battle wage gap indeed, however laws and regulations around the gig economy have to be more inclusive in not only Europe and the United States, but all over the world to make gig economy a more fair environment. Additionally, the decrease of gender bias and increase of diversity in traditional workforce will help make the gig economy more welcoming for all genders.

REFERENCES

Kagnicioglu, D. (2017). The Role of Women in Working Life in Turkey. WIT Transactions on Ecology and The Environment, pp.354-357.

Lowen, M. (2018). Women stand up for right to work in Turkey. [online] BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-43197642 [Accessed 20 Sep. 2019].

Sinden, E. (2017). Exploring the Gap Between Male and Female Employment in the South African Workforce. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 8(6), pp.37-51.

Statistics South Africa (2018). Quarterly Labour Force Survey. [online] Pretoria: STATS SA, pp.5-10. Available at: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02112ndQuarter2018.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep. 2019].

The World Bank (2019). Labor force, female (% of total labor force). The World Bank, p.1.

Trading Economics (2019). Unemployment Rate. [online] Available at: https://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/unemployment-rate and https://tradingeconomics.com/turkey/unemployment-rate [Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].